Bay grasses see record gains in salty waters, offset by losses in central region

The following story originally appeared on the website for William & Mary’s Batten School & VIMS. – Ed.

A key health indicator for the nation’s most economically important estuary has delivered mixed news, with researchers from William & Mary’s Batten School & VIMS reporting a 1%, or 641-acre, annual decline in submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) coverage in the Chesapeake Bay. The estimated 82,778 acres of seagrass meadows included record-breaking gains in salty regions that were offset by mid-bay losses.

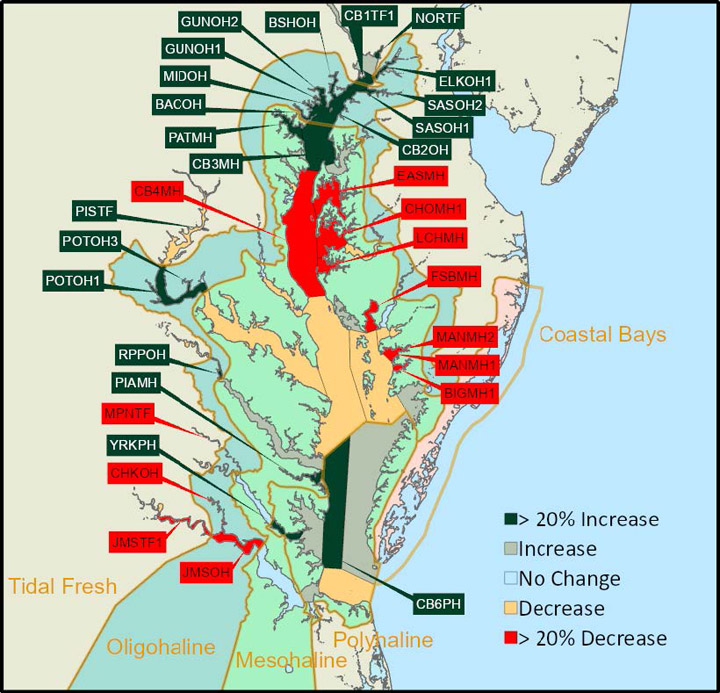

At 64% of its 2025 restoration target and 45% of its long-term goal of 185,000 acres, the bay remains “off course” to meet the management goals established by the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP). SAV coverage is assessed in four different salinity zones, each with its own coverage target, and the results revealed distinct stories in each area.

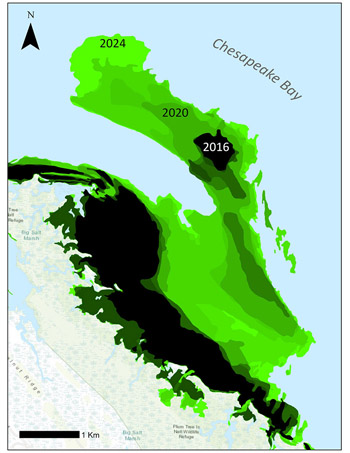

The standout success story comes from the Polyhaline Zone, which represents the saltiest waters stretching from the mouth of the Bay through the lower mainstem. Researchers mapped 24,800 acres of SAV in this zone, a historic high and a 14% increase over 2023. This is the most SAV observed in this zone since annual mapping began in 1984 and represents 74% of the regional target.

Much of the growth occurred in Mobjack Bay, Poquoson Flats as well as areas surrounding Maryland’s Western Shore. These gains were primarily driven by eelgrass, a species that suffered dramatic losses in hot summers of 2005 and 2010 and again during the historically rainy year of 2019 but has rebounded in recent years as water clarity has improved.

“It’s just been amazing to watch the expansion of the meadows. We now have eelgrass happily growing at 8-9 feet at low tide in some places, which was unthinkable just a few years ago. But beyond the polyhaline, it’s another example of how incredibly fast SAV can expand and recover when conditions are right,” said Christopher J. Patrick, associate professor and director of the SAV Program at William & Mary’s Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences & VIMS. “We saw the same story in the Susquehanna Flats 15 years ago. It shows that recovery isn’t incremental, it’s rapid when it happens, and that gives me hope for us achieving the Chesapeake Bay-wide goals in the future even if they seem far off now.”

Gains offset by mesohaline losses

The survey results also showed progress in the Tidal Fresh and Oligohaline Zones. Grass beds increased 2% to 20,218 acres in the Tidal Fresh Zone, achieving 98% of the area’s 20,602-acre target. The slightly salty Oligohaline Zone saw a significant 38% increase from 2023, growing from 3,422 acres to 4,730 acres and reaching 46% of its target. These gains were driven by recoveries in tributaries like the Sassafras, Gunpowder, Back and Middle Rivers, as well as the upper Potomac.

Despite these positive trends, the mid-Bay Mesohaline Zone — the largest and most ecologically diverse region — experienced a 14% decline. This region, dominated by widgeon grass, fell from 38,371 acres in 2023 to 33,031 acres in 2024, meeting just 27% of its 120,306-acre target. This drop coincides with heavy freshwater inputs in that region that delivered high nutrient loads and dropped salinity levels.

Losses were most pronounced along Maryland’s Eastern Shore, especially in the Choptank and Little Choptank Rivers and Tangier Sound.

“Despite many environmental pressures on the bay, we continue to see signs of resilience and recovery in our underwater grasses. The increases in SAV acres observed in three of the four salinity zones this year are truly a testament to the effectiveness of long-term nutrient reductions and collaborative restoration efforts. But as seen with the losses in the mid-Bay, we must remain vigilant,” said Brooke Landry in a CBP press release. Landry is chair of the CBP’s SAV Workgroup and SAV program chief at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

She added, “SAV recovery is not guaranteed. Sustained investment in science-based management, conservation and public engagement will be essential to protect and accelerate not only the recovery of SAV but the entire Chesapeake Bay.”

Overall trends and ecological significance

The Batten School & VIMS established its SAV Monitoring & Restoration Program in 1978. In 1984, following the original Chesapeake Bay Agreement, a partnership was established with the CBP in which the annual aerial survey became the benchmark for SAV restoration goals.

Since that time, underwater grasses in the Bay have more than doubled in coverage, thanks in large part to nutrient reduction requirements established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under the 2010 Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load.

SAV not only provides essential habitat for many of the Bay’s most economically and recreationally important species, it also helps protect shorelines, controls erosion, filters nutrients and sequesters carbon. Because it responds quickly to changes in water quality, SAV is considered one of the best indicators of overall Bay health.

Recent research also points to an ongoing shift from eelgrass to widgeon grass as the dominant SAV species in the Bay, likely due to long-term warming trends. Patrick and other Batten School & VIMS scientists are working to quantify the potential ecological implications of this change. One published finding is that widgeon grass is more prone to crashes following wet springs than eelgrass, a pattern that matches the widgeon grass drop observed in the Mesohaline in 2024.

While the Bay is off course to meet its 2025 goals, the CBP has released a draft of the revised Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement that proposes new zone-specific targets for SAV recovery. It proposes a potential increase in the Bay-wide goal from 185,000 to 196,000 acres, and a new interim target of 95,000 acres by 2035. Public comment on the draft is open through Sept. 1 and can be provided through the CBP’s Beyond 2025 webpage.

More information about the SAV program at William & Mary’s Batten School & VIMS, including the full 2024 SAV report and interactive maps, is available online.