History in hindsight

The following excerpt is from a story that originally appeared in the spring 2025 issue of the W&M Alumni Magazine. – Ed.

Warning signs appeared early. They were evident to the world long before crowds at the 1936 summer Olympics in Berlin displayed “heil, Hitler” salutes. Before Germany invaded Poland on sept. 1, 1939, and England and France declared war soon afterward. Before air-raid sirens blared during the London blitz, and Jewish residents were forced into ghettos in eastern Europe. Before millions of Jews were deported to concentration camps in crowded cattle cars.

An editorial in William & Mary’s student-run Flat Hat newspaper on April 4, 1933, sounded an alarm about censorship: “The Hitler government has clamped a rigid barrier upon the sending of news stories to other nations.”

It was just over two months since Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany and began forming a one-party dictatorship. Appearing under the headline “The Pogrom Program,” the Flat Hat editorial followed reports of Hitler’s Nazi Party organizing a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses on April 1, 1933.

While the editorial acknowledged anti-German bias from some of the external news sources, the writer was troubled by the treatment of Jewish citizens and concluded, “There can be little doubt that race hatred in all [its] most malignant forms is rampant in the Reich.” The editorial writer foresaw dark days ahead for Germany: “No nation, people or government can sow the seeds of hatred, bigotry, oppression, persecution and cruelty, and not be called to account sooner or later. The reckoning that they will pay will probably be in the form of bloodshed.”

The Flat Hat editorial is one of about 55,700 articles included in a United States Holocaust Memorial Museum project coordinated by Eric Schmalz ’10, a former William & Mary history major and Monroe Scholar. Titled “History Unfolded: US Newspapers and the Holocaust,” the project looks at how newspapers across the country covered specific events in the 1930s and ’40s with the goal of understanding what Americans might have known about the Holocaust during that time.

When the museum launched “History Unfolded,” Schmalz says, “there was a misperception that Americans in the 1930s and 1940s knew hardly anything about how Nazis persecuted Jews until the liberation of the concentration camps, or didn’t have access to that information. The museum wanted to test that hypothesis and ask how local newspapers were actually reporting on this. Up to that point, a lot of research had looked at larger newspapers. But we didn’t know as much about smaller daily and weekly newspapers. The research typically wouldn’t include places like Williamsburg, or like rural Iowa or Alaska.”

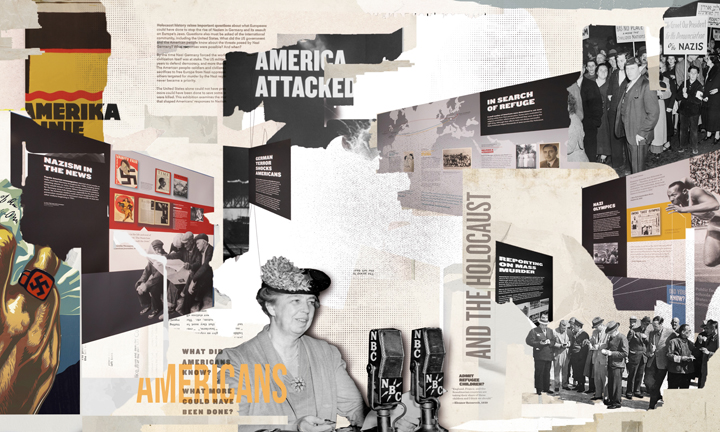

Over a nearly eight-year period, more than 6,400 high school and college students and adult citizen historians across the country contributed articles from their community libraries, historical societies and archives. Their research resulted in a searchable digital database at newspapers.ushmm.org. The “History Unfolded” project helped to inform parts of the museum’s ongoing “Americans and the Holocaust” special exhibition in Washington, D.C., and a related traveling exhibition. The project also provided material for the 2022 PBS documentary film “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” directed by Ken Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein.

The project, exhibition and documentary provide insights into what people in the United States knew about the threats posed by Nazism. Domestic conditions in the United States, including unemployment during the Great Depression and national security concerns, as well as antisemitism and racism, shaped Americans’ responses, Schmalz says. Now, 80 years after the end of World War II in Europe on May 8, 1945, democratic nations still wrestle with how to respond to international crises — and what their responsibility should be to people displaced by violence and persecution.

The museum avoids drawing parallels to current events, however, Schmalz says: “We find it is much more powerful to present the history and then allow people to draw relevance and make the connections themselves. Our curator of the exhibition often says we don’t tell people what to think, but what to think about. And I love that.”

‘History from below’

As someone who grew up in the Washington area’s Northern Virginia suburbs visiting museums and Civil War battlefields, Schmalz says he’s always been interested in history, but he had little concept of what historians do until he got to William & Mary. “I thought that the way historians did their work was they looked at other historians’ books, and they essentially rewrote them,” he says.

Classes he took with history professors such as Philip Daileader changed that perception: “Professor Daileader would get us to think critically about the past and history, and he would say, ‘If I could create as much doubt in you as humanly possible, I have done my job.’ The notion was to be a critical analyzer of historical documents and not to take anything just immediately on face value.”

Most influential for Schmalz was Lu Ann Homza, the James Pinckney Harrison Chair and Professor of History, who encouraged his interest in early modern European history, church history and Reformation studies. He recalls Homza showing him how to look up original documents about early church reforms on microfilm at Swem Library.

As a Monroe Scholar, Schmalz had an opportunity to spend part of the summer after his sophomore year delving further into the archives at Swem and exploring resources at the Library of Congress and Catholic University of America. The next spring, when he was in a study abroad program in Toledo, Spain, Homza invited him to join her in Pamplona as one of three students doing archival research funded through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

“I was studying the 16th-century church in Spain and some of the issues that parishioners were having,” he says, adding that priests were often absent because they divided their time among multiple parishes. “It was so fascinating. I remember holding those original documents in my hands and thinking, ‘What an incredible experience.’”

Schmalz investigated “history from below as well as history from above,” Homza says. “He could read treatises by important theologians and bishops in Spain in the 16th century, but then he could also go to Pamplona and look at complaints by parishioners in tiny villages about their local priests, and how they really wanted their bishop to step in and help them with a priest who was not saying Mass correctly or who was drinking or gambling too much. That showed a side of Catholicism to him that I don’t know if he had been aware of yet in terms of the challenges that the Catholic Church was facing in those moments in time.”

That research background later helped Schmalz secure a job at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2015 as the citizen history community manager for the “History Unfolded” project. After receiving a master’s degree in education from the University of Virginia, Schmalz taught high school history for about three years. When he read the museum’s job listing, he saw an opportunity to blend his research interests and background as an educator.

“They wanted somebody with teaching experience who had done historical research and knew how to look into archives and databases,” he says. “What I thought was so cool when I saw that job description and when I interviewed was a specific project goal to help develop students’ research and analysis skills — and to foster a love of history.”

Homza sees Schmalz as well suited for his role at the Holocaust Memorial Museum. “It’s the best of both worlds in a lot of ways,” she says. “He gets to do what we call public-facing history and have an impact on the communities with whom he’s communicating, and also still do all the research that he loved to do when he was an undergraduate.”