Coping with a painful childhood

College can be a joyful time — of learning, forming lifelong friendships and having fun. But it’s not without its challenges. National Collegiate Alcohol Awareness Week, Oct. 19-25, brings attention to the struggles faced by students on campuses across the U.S., calling for increased education and resources.

At William & Mary, Associate Professor of Psychological Sciences Adrian Bravo ’12 expands that work. Collaborating with an international team of researchers and undergraduate students, he’s teasing out the cross-national trends that might explain why certain students are more vulnerable to alcohol use disorders. A recent publication in Substance Use & Misuse, with W&M alumna Isabela Ortiz Caso ’25 as lead author, points to adverse childhood experiences as a widespread culprit.

“Adverse childhood experiences aren’t restricted to the horrible extremes of physical and emotional abuse,” said Bravo. “Seeing parents or siblings constantly argue, growing up with a family member who struggles with an alcohol use disorder or feeling unloved and neglected can also deeply impact someone’s identity and understanding of the world around them.”

While the study doesn’t prove causality, it reveals a clear chain of correlations connecting childhood adversity, ruminative thinking, drinking to cope and negative alcohol-related consequences.

Importantly, the study demonstrates that this pattern isn’t restricted to one geographic or cultural setting. Over 4,000 students from 12 universities in seven countries — among them Argentina, England, the U.S. and South Africa — were included in the researchers’ analysis.

“Most psychology studies focus on a single population,” said Ortiz Caso. “But we found the same pattern across seven countries, suggesting that the factors linked to problematic drinking transcend geography — and that insights from this work could help public health officials shape global harm-reduction strategies.”

The Cross-Cultural Addictions Study Team

As a Cuban immigrant to the U.S., Bravo has always been interested in the cultural and legal norms surrounding alcohol and drug use in different countries. As he entered his doctoral work, he reached out to several researchers outside the U.S., asking to start a collaboration that would pool their international expertise to investigate questions of alcohol and drug misuse. They accepted, and the Cross-Cultural Addictions Study Team (CAST) was born.

Today, the collaboration includes 18 researchers from seven countries.

“The primary goal of CAST is to understand how prior experiences or individual personality differences place some individuals at higher risk for substance use and mental health problems,” said Bravo. “Interestingly, our research shows that many factors other than simply drinking too much predict who reports negative alcohol-related problems while in college.”

For Bravo, that finding underscores the need to move beyond solely measuring how much students drink and instead focus on the psychological and behavioral factors that drive problematic use — both on U.S. campuses and globally.

Over the course of four CAST studies, Bravo has been intrigued to find that three key factors indicating risk for problematic drinking are conserved across multiple countries.

“The first is impulsivity, which often manifests as a sense of urgency — a need to act immediately when emotions run high,” he said. “That urgency can drive drinking both to celebrate success and to soothe disappointment.”

The second factor can be broadly labeled as poor mental health.

“For those suffering from poor mental health, especially students who tend to fixate on negative feelings, on the causes and consequences of what’s occurring to them, turning to substances may seem like the quickest and easiest way to deal with those feelings,” said Bravo.

The final of the big three factors is what Bravo calls adverse childhood experiences, ranging from physical abuse to neglect to a volatile home environment with arguing and uncertainty. This factor is the focus of the recent paper, “Risky Family Environment, Rumination, Drinking to Cope, and Problematic Alcohol Use: A Cross-National Examination Among College Students,” which was led by Bravo’s former research student Isabela Ortiz Caso ’25.

The impact of childhood experiences

Like Bravo, Ortiz Caso, who now works as an intramural research fellow at the National Institutes of Health, came to the U.S. from Cuba and shares an interest in studying cross-cultural differences. As a freshman at William & Mary, she joined the Bravo Lab after learning about his research through the W&M Scholars Undergraduate Research Experience (WMSURE), a program providing support and faculty mentorship for undergraduates conducting research.

Demonstrating a knack for research and an eagerness to craft her own project, Ortiz Caso proposed and led the study recently published in Substance Use & Misuse under Bravo’s supervision, collaborating with other undergraduates in his lab. Support from The Margaret S. Glauber Faculty-Student Research Fellows and Scholarship Fund, founded thanks to Margaret “Maggie” Glauber ’51, helped fuel her research.

“I was really interested to see if risky family environments, with a lot of hostility and aggression, would correlate with negative alcohol-related consequences,” she said. “So it was really exciting to obtain research results showing a statistically significant relationship between these factors across so many geographies.”

For Ortiz Caso and her collaborators, establishing this widespread pattern is critical to informing interventions that could help treat alcohol misuse among college students.

“When people drink to cope with negative emotions — sometimes shaped by early life experiences — it’s a very different motivation than social drinking,” she said. “Rather than responding to peer pressure, they’re using alcohol to manage or escape what they feel inside.”

Identifying and better understanding drinking motivations can help policymakers, universities and college students deploy more effective strategies to deal with alcohol use disorders, says Ortiz Caso.

Both Ortiz Caso and Bravo encourage universities to help students struggling with alcohol use problems by offering clear, continual education and accessible resources.

Through William & Mary’s Health & Wellness offerings, including Campus Recreation, the Counseling Center, Health Promotion and the Student Health Center, students, faculty and staff can access resources that promote wellbeing and help to prevent and reduce risk related to substance use.

Additional resources are offered across campus, including at the W&M School of Education, which offers the New Leaf clinic, part of the Flanagan Counselor Education Clinic, as a resource for students struggling with high-risk substance use. Faculty and staff also have access to the Employee Assistance Program, which offers a wide range of counseling support.

“When trying to help students, universities shouldn’t just tell students that they need to drink less or drink safer,” said Bravo. “They need to provide students who are turning to alcohol or drugs to destress with substance-free alternatives. These could include meditation, exercise, counseling — accessible resources to break the cycle of maladaptive coping and give these students a better chance to develop healthy habits.”

Latest W&M News

- The summer of cyber: W&M students gain real-world experience in cybersecurityWilliam & Mary students had a number of opportunities this summer to make contributions to the nation's cyber capabilities.

- W&M’s Center for Gifted Education expands pre-collegiate summer campsOfferings strengthen access and year-round support for Virginia students.

- Raft Debate 2025: Who will keep their spot on the raft?The beloved W&M tradition returns Oct. 28 starting at 6 p.m. in the Sadler Center’s Commonwealth Auditorium.

- An average year for juvenile striped bass in Virginia waters in 2025Preliminary results from an ongoing long-term survey suggest that an average year class of young-of-year striped bass was produced in the Virginia tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay in 2025.

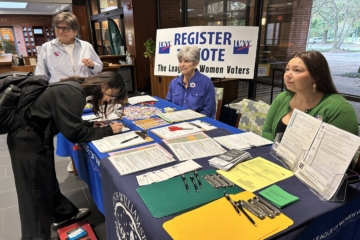

- Helping students fulfill their civic dutyAs part of its commitment to democracy, W&M is dedicated to helping students, faculty and staff participate in elections.

- Uncovering layers of historyAs part of the team uncovering the foundations of the historic Williamsburg Bray School, Heather Little M.A. ’23 and Madeline Dorton ’24 are unearthing the history of the campus where they studied history and archaeology as students.