Rising from the ashes

The following story excerpt is from the spring 2025 issue of the W&M Alumni Magazine. – Ed.

As the frequency and intensity of wildfires accelerate, William & Mary faculty, students and alumni are stepping up to tackle this critical issue. By promoting healthy land management practices, training the next generation of wildland firefighters and engaging in research and philanthropic initiatives, the W&M community is ensuring healthier communities and ecosystems.

Jonathan “Jon” Layne ’75 wasn’t at home in his Pacific Palisades, California, neighborhood when uncontrolled wildfires broke out across Los Angeles in early January. He and his wife, Sheryl, were almost 7,000 miles away on a cruise to Antarctica that they had booked over a year earlier.

While on board the cruise ship, the Laynes received updates with nearly unbelievable descriptions of destruction. “We kept getting new reports,” he says. “Our grocery store — gone. Our bank — melted. Our grandkids’ school — destroyed.”

First, the Laynes needed to know that their family was safe. When they finally connected with their adult children, Scott and Shelby, who also live with their families in Pacific Palisades, they learned that Scott and Shelby’s families had safely evacuated but that both of their homes had been burned to the ground.

Satisfied of his family’s safety, Layne was still unsure about his own house. By checking the app connected to his electric vehicle, he could tell that the temperature inside the car, parked in a garage connected to his house, ranged from about 60 to 70 degrees. That gave him hope that his house was still standing.

He was right: After returning to LA two weeks later, Layne found his home severely damaged but not destroyed. He later spoke with other electric vehicle owners who had left their homes during the fires and who had similarly used apps to assess the danger to their property. When the temperatures in their cars soared from 70 to 80 to 90 to 100 degrees before losing the signal, the owners knew their cars — and, therefore, their homes — had burned.

Being on the other side of the world during the LA fires was unsettling for Jon and Sheryl. “There was a keen juxtaposition of the serenity, beauty and awe-inspiring landscape of Antarctica with the pain and suffering and loss of life and property that our family and community were going through in LA,” Layne says.

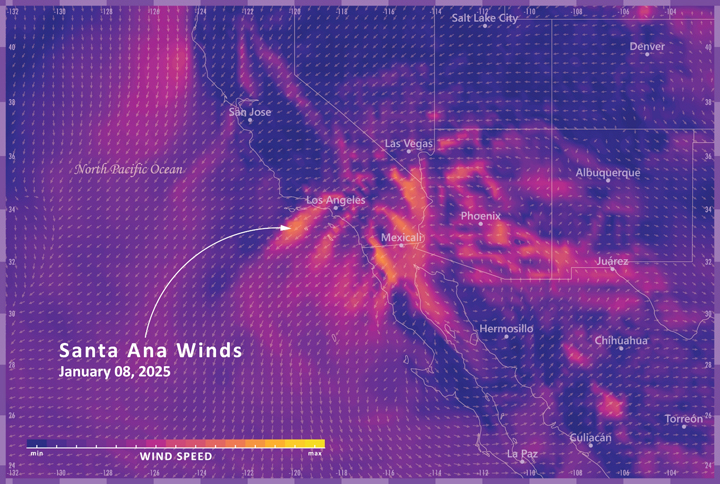

The exact reason for the start of the LA wildfires remains unclear. Some point to improperly grounded wires or downed transmission towers for the initial spark, but it was a combination of natural conditions that caused the fires to grow out of control. Limited rainfall during the previous year contributed to brittle vegetation, which can easily catch fire. The fires were further fueled by Santa Ana winds blowing at 100 mph from the deserts east of LA toward the western coast.

Infrastructure and public service issues also contributed to the magnitude of the devastating fires. Damaged reservoirs in the city hadn’t been repaired, leaving firefighters without enough water flowing through hydrants. Cutbacks in the Los Angeles Fire Department’s budget meant fewer personnel and less equipment. And the fire department’s fixed-wing airplanes were grounded because the high winds were too dangerous for the pilots, leaving them unable to fight the fires from the sky.

When the Laynes visited their house in the fires’ aftermath, they were astounded at the level of destruction in their neighborhood. Fire had gone right up their driveway, and the house was covered with ash and soot. “Our house smelled like a barbeque pit,” Layne says.

But they were the lucky ones. Their house was still standing while the rest of their neighborhood was gone. Layne compares the scene to photos of the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, in 1945.

“Block after block, every home is wiped out,” he says.

The lost homes were devastating for residents, but other losses were even more painful. When the Laynes’ children fled their houses, they didn’t have enough time to grab any possessions. Birth certificates, social security cards, wedding licenses, family photos — all are gone.

With property and capital losses estimated between $76 billion and $131 billion, according to UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, the task of rebuilding is enormous, especially in hardhit areas like Pacific Palisades and Altadena. Yet there has already been an outpouring of support.

Hats and sweatshirts with the slogan “Pali Strong” reflect the Pacific Palisades community’s resilience and motivation to push forward. Neighbors are organizing recovery efforts through Zoom meetings and webinars. Residents have had to become well-versed in subjects they previously knew little about, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) which leak into air and water supplies from burned pipes.

“We’re all very resilient,” Layne says. “Our community will rebuild.”

Protective fire

Uncontrolled wildfires bring unimaginable devastation. In the early 20th century, effective marketing strategies like Smokey Bear and the Disney movie “Bambi” attempted to reduce human-caused wildfires. These strategies were so effective, however, that the U.S. public came to view fires primarily as negative anomalies.

Bobby Clontz ’89, statewide fire manager and longleaf pine specialist at The Nature Conservancy, would like to change that perspective.

It’s time for a new era in the public’s perception of fire, Clontz contends, one in which people recognize fire as a normal and essential component of healthy ecosystems.

Fire is meant to be on the landscape. For millennia, it was a chronic presence, whether through lightning strikes or Native American burning practices that managed wildlife and agriculture. But environmental changes such as drought and rising temperatures, combined with an overemphasis on fire suppression in the 20th century, have led to dangerous levels of uncontrolled fires.

Research from the National Interagency Fire Center shows that factors including warmer springs and drier summers have lengthened wildfire seasons in many areas. Worldwide, the frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires have more than doubled over the past 20 years, according to a study of satellite data published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Land management techniques allow fire to play its natural role in keeping ecosystems healthy while minimizing the danger to people and property. One of those techniques, practiced by Clontz and The Nature Conservancy, involves conducting prescribed burns, which are deliberately planned and carefully supervised by fire management officials.

Managing a prescribed burn is markedly easier than fighting a wildfire. “For a prescribed burn, planning and preparation is completed ahead of time,” Clontz says. “The fire lines have been prepared in advance, and we’ve notified close neighbors, fire departments and, when required, received permits from regulatory agencies. Importantly, we have chosen the desired weather conditions, and we don’t burn until the suitable weather conditions are forecasted.”

That careful planning stands in stark contrast to the rapidity of a wildfire response.

“In a wildfire, we don’t have the advantage of preparation. We are concurrently working to extinguish a wildfire while assessing weather, rate of spread and whether we have enough firefighters and engines, while also determining the risks to neighbors and traffic safety,” Clontz says.

When a wildfire breaks out in an area that’s recently had a prescribed burn, the fire will burn at a lower intensity and may burn itself out because of the reduced amount of debris.

“Used strategically,” Clontz says, “prescribed fire can be a very effective protective measure for people.”

In his role at The Nature Conservancy, Clontz uses prescribed fire as a tool for positive ecological outcomes, since many species evolved with fire and therefore developed adaptations to, or even a dependency on, fire.

The longleaf pine tree, for example, is a species that evolved with fire and requires regular burnings to maintain its health by removing brush competition. Native to the Southeastern United States, the longleaf pine’s range had collapsed from about one million acres in Virginia before 17th-century European settlement to only 200 individual trees by the 1990s. With careful ecological management, including regular prescribed burns, the longleaf pine range has been brought back to about 8,000 acres in Southeastern Virginia.

Clontz gravitated toward nature and the outdoors since his childhood on the Days Point peninsula near Smithfield, Virginia. His father and uncle were both outdoorsmen who showed him the beauty of nature. Clontz accompanied his uncle, a biologist for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, on adventures that once included taking measurements of a wild bear the department was studying. And his father, a watercolor painter, focused his art on waterfowl and marsh scenes.

“Between the two of them, I got to see the landscape through the eyes of a biologist and the eyes of an artist,” Clontz says.

When he arrived at William & Mary, Clontz was unsure of his direction, thinking that he’d perhaps pursue a major in business. But after a few semesters, he followed his passion for the outdoors toward an environmental science degree. Mitchell Byrd, director emeritus of the Center for Conservation Biology and Chancellor Professor Emeritus of Biology, and the late biology professor Ruth Beck were two of his most influential professors.

Clontz joined Beck’s group that traveled each spring to Grandview Nature Preserve in Hampton, Virginia, to post signs protecting the nesting areas of shorebirds. During the summer after graduation, he worked for Byrd as a hack site attendant, protecting and releasing peregrine falcon chicks.

Clontz enjoyed the ornithology work but knew his true interests were in the wetlands he had grown up around. He enrolled in a master’s program at Duke University, home of the renowned Wetland Center, and soon visited wetlands that recently had been burned.

“That was my introduction to fire ecology and the incredible diversity of plants that exist at this intersection of fire and wetlands,” he says.

After working in various consulting roles across North and South Carolina, Clontz joined The Nature Conservancy for a short-term internship in 2003 and as a full-time employee in 2007.

“When I came to the Conservancy, I was hired as a land steward to manage a site with red-cockaded woodpeckers that I had first learned about in Dr. Byrd’s class,” Clontz says.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers, an unusual species that excavates its cavities in live pine trees, had hit rock bottom in Virginia in 2002, with only two breeding pairs left in the state. Revitalizing the Virginia ecosystem, including bringing fire back to the landscape, has increased the number of red-cockaded woodpeckers to 94 as of December 2024.

Read the full story on the W&M Alumni Magazine website.

Latest W&M News

- W&M to preserve President’s House for future generationsThe board will explore possibilities of transforming the university’s historic President's House into space that remains central to the life of the university.

- An extraordinary year for William & MaryRecord-breaking philanthropy positions William & Mary to lead.

- America’s Tapestry project underway at the Muscarelle Museum of ArtThe project marks the 250th anniversary of the nation’s founding through the creation of 13 original tapestries designed to tell a unified story of the nation.

- College of Arts & Sciences launches new name, celebrates the people of the CollegeNew name reflects a bold vision, deep roots and the people shaping the future.

- Another bumper crop of Fulbright Scholars from W&M prepares to head abroadWilliam & Mary's global reach has been confirmed once again as nine recent graduates and alumni received highly selective Fulbright Scholarships.

- Can a parasitic worm help rebuild blue crab populations in the Chesapeake Bay?A new study published in the journal PLOS One by researchers at William & Mary’s Batten School & VIMS suggests parasitic worms could serve as a valuable biomarker for managing the fishery.